The Saudi-led campaign against Qatar has put Turkey in a difficult position due to Turkey’s increasingly warm relations with Saudi Arabia over its Syria and Iraq policies. Understanding that it does not have enough power to play the sole mediator role in this very heated atmosphere, Ankara sided with its long-term political ally, Qatar. Turkish food supplies have also been rushed to Doha with the support of a strong media campaign. More importantly, Turkey’s parliament swiftly authorized the deployment of Turkish troops—currently up to 3,000 soldiers—in the country. Although this agreement was signed in 2014, the step of fast-tracking implementation is interpreted as a strong willingness to defend Qatar against a potential coup d’état; the approval document authorized Turkey to assign as many military personnel as needed to train Qatari forces “in internal security.”

The top Turkish diplomats’ hurried visits to the Gulf countries highlight how Ankara perceives a real threat in the case of a deepening conflict among members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Although President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan called the blockade “inhumane and against Islamic values,” Turkey is pursuing a very cautious approach in avoiding criticism of the Saudi regime. Erdoğan recently noted Turkey’s past offer to set up a military base in Saudi Arabia, highlighting that the Turkish base in Qatar is no threat to the kingdom. Erdoğan’s hint that King Salman had agreed to consider Turkey’s offer, however, prompted Riyadh to release a strong statement rejecting the claim.

Following the official line, Turkey’s pro-government media presented the current Gulf rift as an American plot and accused the US president of sowing divisions in the Muslim world. Given that the Turkish government has sought to discourage criticism of US President Donald Trump, such a discursive shift is remarkable. Erdoğan repeatedly implied that the crisis is part of a major conspiracy that targets Turkey.

There are three major drivers that shape Ankara’s policy toward the Gulf crisis: (1) fear that the allegations against Qatar, such as supporting the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas, could be directed at the Turkish government in the long term; (2) financial concerns that stem from Turkey’s increasingly fragile economy; and, (3) potential harmful consequences regarding Turkish calculations in Syria and Iraq.

Is Turkey the Next Target?

Not surprisingly, Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi called for Gulf leaders to boycott Turkey for supporting Qatar. The call taps into an already growing sentiment in Ankara that the Erdoğan regime is being impacted by the Qatar blockade. Ankara and Doha have long shared similar foreign policy perspectives; their joint support for the Muslim Brotherhood, in particular, has raised eyebrows in the GCC leadership—which had designated the group as “terrorist” after the Egyptian coup in 2013.

Although the current crisis is unprecedented in many respects, the Gulf’s pressure against Doha has previously pulled Ankara into a contentious political game. In March 2014, for example, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain withdrew their ambassadors from Doha, demanding Qatar’s cessation of support to the Muslim Brotherhood. Although tensions were eased within a few months, Qatar maintained its independent foreign policy by further deepening ties with Turkey. In December 2014, Doha and Ankara signed a military agreement for deployment of Turkish troops on Qatari soil—developing their previous defense industry cooperation agreements of 2007 and 2012.

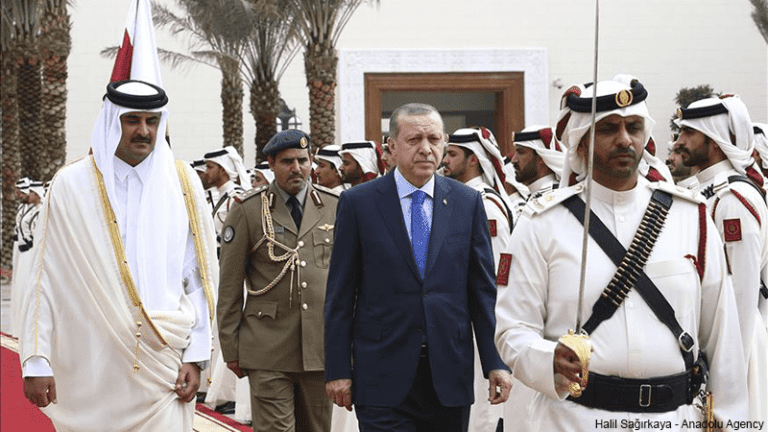

The Syrian civil war made Turkey and Qatar even closer. Both provided strong support to the Syrian opposition and also to each other. Following Ankara’s spat with Moscow over the downing of a Russian jet in Syria, Doha offered about $3 billion in financial support to make up for Turkey’s loss of Russian tourism. It also promised gas export guarantees if Moscow decided to withhold natural gas supplies to punish Ankara. Such close cooperation reached its peak as the Turkish president and the Qatari emir cultivated personal bonds through frequent meetings in Turkey.

Hence, if Doha gives in to the pressure, Ankara may face increasing isolation in regional diplomacy. After all, the very accusations that put Qatar on the spot may well be used against the Erdoğan regime. Turkey, however, already feels the heat as the Saudi-led GCC is a prized economic partner. Extended instability in the Gulf region means greater negative consequences for the Turkish economy.

Turkey’s Indispensable Economic Ties to the Gulf

Turkish economic concerns are largely behind Ankara’s cautious approach toward Saudi Arabia. A prolonged crisis could jeopardize the prospects for a free trade agreement between Turkey and the GCC, one that was expected to be signed at the end of 2017. Moreover, Ankara has entered the lucrative Gulf defense sector, hoping to sign a major defense export deal with Saudi Arabia. Thus, compared to Qatar’s financial significance to the Turkish economy, the Saudi-led bloc is equally important. For example, while Qatari foreign direct investment (FDI) amounts to $1.5 billion, total Saudi and Emirati FDIs are over $6 billion. Considering foreign long-term loans for the Turkish private sector, Bahrain is the lead Gulf lender with $11 billion, whereas Qatar is not a player in this regard.

Turkey’s dwindling tourism sector and economic slowdown make Gulf money even more important. At present, some Saudi tourists have begun to cancel their visits to Turkey for the Ramadan Eid holiday. Earlier, in January 2017, the pro-government Turkish media boasted that Erdoğan’s Gulf tour was an economic success, ushering in a new $20 billion investment from the Turkish-Gulf fund generated by Saudi and North American investors. Erdoğan had hoped that his victory in Turkey’s nationwide referendum could bring financial stability; ironically, however, the referendum results have emboldened the opposition in major cities including Istanbul—the economic hub—where Erdoğan lost for the first time since becoming the mayor of the city in 1994. This is significant because the new presidential system will come into effect only after the 2019 parliamentary elections, and some analysts expect that Erdoğan may even call early elections in 2018 to ensure his party’s victory in parliamentary seats. In any event, given the extremely polarized political atmosphere toward such critical elections, avoiding a crash in the highly fragile Turkish economy will remain a priority for Erdoğan in the near future.

Ankara’s Strategic Concerns: A Nail in the Coffin of Neo-Ottomanism?

Turkey’s involvement in the Syrian civil war has shaped its strategic calculations in the Middle East. One of the most noticeable policy changes was Turkey’s increasing resentment toward Iran and its rapprochement with Saudi Arabia. Ankara’s policy in Iraq was perhaps the best showground to watch such transformative relations. In fact, in remarks after the referendum victory in April 2017, Erdoğan criticized “Persian expansionism” in the Middle East; a few months before, he had exchanged in a verbal spat with Iranian officials. Most tellingly, Erdoğan repeated his verbal attacks against Iran regarding “Persian expansionism in Syria and Iraq” in a recent interview, in which he calls for Saudi Arabia to “show its leadership,” and thus, to put an end to the Qatar crisis. The fact that Ankara reminds Riyadh of the two countries’ growing and shared interests in the region indicates how damaging the Gulf crisis may be to Turkey’s regional aspirations, if it persists.

Although the Gulf crisis may prompt renewed Turkish-Iranian reconciliation, there are strong limitations. Geopolitical calculations dictate Ankara-GCC cooperation in Iraq, including the Iraqi Kurdistan region. Saudi Arabia perceives Turkey’s influence over Iraq as a bulwark against Iranian expansionism. Ankara declared the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), better known as the Shiite militias, as “terrorists”—despite the fact that the PMF is officially recognized as a legitimate “state-affiliated entity” in Iraq. Baghdad’s tense relations with Ankara were most evident when the Iraqi government demanded the removal of Turkish forces in Bashiqa camp near Mosul. The strong cooperation between Erdoğan and Masoud Barzani, leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party, also irritates Baghdad. The battles over disputed territories in Iraq’s oil-rich Mosul and Kirkuk regions have not only eroded Erbil-Baghdad relations but also hurt Ankara-Tehran interactions.

The limits of Turkish-Iranian cooperation are perhaps most evident in Syria, where the two parties are in an active fight on opposing sides. Ankara has major expectations from the Gulf countries to secure Turkish borders. In his Gulf tour, Erdoğan courted the GCC’s financial support for Syrian refugees, explaining his vision to turn an area of 4,000-5,000 square kilometers into a safe zone where new housing projects would be built. In addition to Washington’s approval, the Turkey-led reconstruction of northern Syria will require billions of dollars and Erdoğan noted that Saudi support would be essential in this endeavor.

In the case of further escalation, therefore, the Gulf crisis will not only harm Turkey-GCC relations but also jeopardize Ankara’s maneuvering capacity in shaping regional politics. Turkey’s domestic troubles have already led to the rise of nationalist bureaucrats, who prefer isolationalist Eurasianism over an active neo-Ottomanism in the Middle East. Some influential Eurasianist circles already expressed[1] their support of Erdoğan’s Qatar policy as long as Russian-Turkish cooperation is enhanced.

Why the Trump-Tillerson Divide Matters for Ankara

For Ankara, Washington’s inconsistent signals regarding the Qatar crisis indicates that Riyadh may be able to reconsider its long-term calculations. While Secretary of State Rex Tillerson called for diplomatic efforts to mitigate the crisis and to ease the blockade, President Trump—only a few hours after Tillerson’s remarks—took a strikingly different approach by accusing Qatar of being “a funder of terrorism at a very high level.”

Ankara views the Saudi leadership as traditionally risk-averse, especially under King Salman’s predecessors, and thus, it sees negotiation with the kingdom as feasible. Although King Salman and his son, Crown Prince and Defense Secretary Mohammed bin Salman, pursue more aggressive policies, the costly war in Yemen may cause the Saudi elite to step back indeed. Given that Iran would exploit a dysfunctional GCC and could even trigger protests in Bahrain, the stakes are too high for Riyadh—especially at a time when Washington’s policies are not consistent. The first indication of de-escalation was the statement by Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister, Adel al-Jubeir, that the kingdom was preparing a list of grievances, “not demands,” from Doha.

The divide between President Trump and the Department of State, however, signals a bumpy road ahead. Facing increasing domestic pressure, Trump appears to be susceptible to special interest groups in Washington—especially those supporting the bill in the US Congress which designates the Muslim Brotherhood as a foreign terrorist organization. By shunning Qatar due to its relations with the Muslim Brotherhood, Washington may open the proverbial Pandora’s Box. Tillerson recently admitted that the violent groups affiliated with the Brotherhood had already been added to the US terrorism list and that peaceful elements of the group have become parts of the governments in the region. The guilt by association with the Brotherhood could even hurt Bahrain, which cut diplomatic relations with Qatar and expelled Qatari military personnel at the US military base there. The fact is that Bahrain’s royal Al Khalifa family’s close ties with the Bahraini Muslim Brotherhood’s political wing, Minbar, is no secret. Similarly, allegations of the Qatar-Hamas link are problematic. Hamas is not considered a terrorist organization by the United Nations and Qatar has cultivated good relations with Hamas’s main rival, the Palestinian Authority headed by Mahmoud Abbas.

In the larger picture, Washington’s incompetence in crisis management complements its fading soft power in the Middle East. Ironically, Trump Administration officials even confess how such weakness is exploited well by Russia. Defense Secretary James Mattis, for example, commented that the Qatar crisis is a sign that Russia is “trying to break any kind of multilateral alliance … that is a stabilizing influence in the world.” Apparently, US diplomatic leadership is missing at a time when it is needed more than ever in the Gulf.

1 Article is in Turkish.