First, Do No Harm: New Canadian Law Allows for Assisted Suicide for Patients with Psychiatric Disorders

Monet/AdobeStock

Dr Komrad has made a video to accompany this article. You can watch the video here. - Ed.

COMMENTARY

Canada just passed a law that radically changes the boundary between acceptable and unacceptable medical practice and has opened a path to euthanasia for patients with psychiatric illness who find their conditions unbearable.

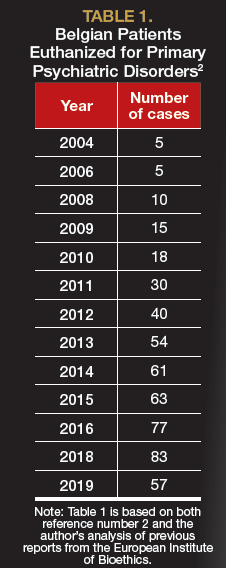

Unfortunately, this is not a new phenomenon. Several countries allow psychiatric patients who are suicidal to voluntarily receive death by lethal injection (euthanasia) or a self-administered prescription for lethal medication (assisted suicide) from physicians. In Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg (collectively known as the Benelux nations) these practices first emerged in 2002, after laws were passed permitting medically assisted death for patients whose physical or psychological suffering was unbearable and could not be effectively treated by acceptable means.1 A terminal condition was not a necessary criterion. This opened the door for some psychiatric patients in those countries to have suicide provided for them rather than prevented. It is documented that between 100 and 200 psychiatric patients are euthanized upon request annually between Belgium and the Netherlands (Table 1 and Table 2).2,3

TABLE 1. Belgian Patients Euthanized for Primary Psychiatric Disorders2

In concerned response to these developments, the American Psychiatric Association issued a position statement in 2016: “A psychiatrist should not prescribe or administer any intervention to a non–terminally ill person for the purpose of causing death.”4

TABLE 2. Patients Euthanized in the Netherlands for Primary Psychiatric Disorders3

The Evolution of Canada’s Bill

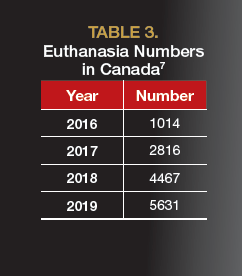

In 2016, Canada passed Bill C-14, a law permitting medical euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, together known as Medical Aid In Dying (MAID).5 By November 2020, more than 13,000 individuals nearing the end of life had been voluntarily euthanized as a result of this bill.6,7

To be eligible, a patient’s natural death must be predicted to be reasonably foreseeable. This uniquely Canadian term was not statutorily defined, but it was understood to be associated with the end of life—how close was undetermined. Because death from mental disorders was not considered to be strongly predictable, mental illnesses were not eligible conditions. This feature of the law essentially prevented the kind of psychiatric euthanasia practiced in the Benelux countries.8

Then, in 2019, a Quebec Superior Court ruling challenged the constitutionality of the reasonably foreseeable restriction.9 As a result, a new federal bill was introduced to extend euthanasia eligibility, without the previous restriction. This new initiative, Bill C-7, followed the Benelux model; it removed the prior exclusion of those who have with nonterminal chronic illnesses and permitted euthanasia for those whose psychological or physical suffering is deemed intolerable and untreatable.10

Initially, Bill C-7 clearly excluded psychiatric disorders, which was at least implicit in the original C-14 law. However, there was ambiguity in this proscription, because psychological suffering (which is not defined in either legislation) continued to be a criterion for eligibility. In addition, many protested that C-14’s scope discriminated against those with mental illnesses. Ironically, in its efforts to promote parity, the Canadian Psychiatric Association was such a voice. As an organization, it declared: “Patients with a psychiatric illness should not be discriminated against solely on the basis of their disability, and should have available the same options regarding MAID as available to all patients.”11

This led to a dramatic turn of events in the (unelected) Canadian Senate, which considered Bill C-7 this February. In an unprecedented move, Senator Stan Kutcher, MD, who is also a psychiatrist, declared that the exclusion of individuals with psychiatric disabilities would be discriminatory. He introduced an amendment allowing MAID for mental illness available within 18 months of the bill passing.12 When the modified legislation was returned to the House of Commons, the discussion was quickly shut down by a liberal coalition and the bloc party from Quebec (a province that promotes euthanasia and aims to restrict conscientious objection to euthanasia by health care professionals). A vote was forced, and on March 17, 2021, the C-7 expansion of euthanasia in Canada became law, complete with the last-minute amendment to sunset the mental illness exclusion after 2 years.13

TABLE 3. Euthanasia Numbers in Canada7

This 2-year interval is to be used to create an expert panel to establish standards for evaluating patients and procedures to distinguish between patients with psychiatric disorders whose suicide should be prevented from those whose for whom it could be provided. However, as Alex Schadenberg, the executive director of the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition, noted in response to a query, “There isn’t a prosecutor in the land who would prosecute someone for doing euthanasia for mental illness before the 24-month time frame has passed because it is technically legal.”

Objections to Psychiatrist-Assisted Suicide

This is a profound change in the trajectory of the euthanasia law, and the practice of psychiatry for Canada, which is now the largest nation that will soon allow MAID for psychiatric conditions. It has rocked the professional mental health community in Canada, which fought to forestall the inclusion of psychiatric disorders for euthanasia.

The latest law is disappointing but unsurprising considering the huge pushes for parity and nondiscrimination at all costs. Unlike the in United States, health care in Canada is considered a charter (constitutional) right. Thus, once MAID became a medical procedure, excluding patients with psychiatric illness from this right was nearly impossible.

Countries that have allowed MAID in a limited number of cases have quickly found themselves descending a slippery slope. Prominent critic Wesley J. Smith, JD, noted, “Once a society embraces doctor-prescribed death as an acceptable answer to human suffering or as some kind of fundamental liberty right, there are no brakes. We need only look at European countries that have gone down the Euthanasia Highway to see how society is impacted deleteriously by accepting killing as a suitable answer to the problem of human suffering.”14 Indeed, Belgium and the Netherlands are now debating the extension of euthanasia beyond medical conditions to include those who feel they have a completed life15 or are tired of living.16 There is even discussion of de-medicalizing euthanasia by providing lethal over-the-counter pills.17 Pegasos, a self-proclaimed “voluntary assisted dying association” based in Basel, Switzerland, currently provides euthanasia for nonmedical “suicide tourists.”18

Many psychiatrists in Canada are deeply concerned by the recent developments. In the face of C-7, the psychiatrist editor of the Journal of Ethics in Mental Health reported19:

A few days ago, a 30-year-old patient with very treatable mental illness asked me to end her life. Her distraught parents came to the appointment with her because they were afraid that I might support her request and that they would be helpless to do anything about it. It’s horrific they have to worry that by going to a psychiatrist, their daughter might be killed by that very psychiatrist.

Similar significant objection comes from the disability advocacy community.20 They are concerned that permitting euthanasia for nonterminal, disabled individuals implies that their lives may be not worth living. Furthermore, they recognize that individuals with disabilities may not have adequate access to state-of-the-art treatment, and that euthanasia could become a cost-saving alternative to suffering when adequate solutions are not available or affordable.

An evaluation by the United Nations also expressed strong worry about how Bill C-7 impacts individuals with chronic disabilities21:

We are deeply concerned that the eligibility criteria set out in Bill C-7 to access medical assistance in dying may be of a discriminatory nature, or have a discriminatory impact. By singling out the suffering associated with disabilities being of a different quality and kind than any other suffering, they potentially subject persons with disability to discrimination on account of such a disability.

There is also strong objection among Canada’s First Peoples, due to conflicts with cultural values, their limited access to state-of-the-art treatments, and staggering suicide rates in that population.22 Similarly, the Canadian Catholic Bishops, who are always opposed to euthanasia, have been left particularly aghast.23

Bill C-7 also sets up a 2-tier system, abolishing some of the original C-14 safeguards. For instance, patients who are terminally ill can be evaluated for euthanasia and possibly receive it on the same day, with no waiting period, unlike the 10-day waiting period in the previous C-14 law. However, patients who are not terminally ill must wait 90 days. Ironically, it is not unusual to have to wait much longer than that in Canada to get psychiatric consultation, treatment, and other resources.

Moreover, there is no requirement that additional, evidenced-based treatments be implemented, although patients are urged to give all treatments serious consideration. Even Belgium, which is known for its liberal approach, recently added guidelines that individuals applying for euthanasia for a mental disorder should not have refused any evidenced-based treatments.24

A group of experts in Canadian law and medicine wrote25:

C-7 will allow physicians to end the life of people with disabilities or chronic illnesses at their request and will require the system to ensure it happens even when physicians are convinced, based on their expert knowledge, that medicine offers options and even when the patient may have years or decades to live with a good quality of life if other options are explored and tried first.

The American Medical Association has concluded that MAID practices are “fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as a healer,”26 and the World Medical Association “is firmly opposed to euthanasia and assisted suicide.”27 Nevertheless, these types of laws have been adopted around the world, most recently in New Zealand, Spain, Portugal, and several states in Australia. In US states, as in Canada, attempts have been made to expand initially strict practices.28 The justifications made in debate for euthanasia and assisted suicide (eg, autonomy, self-determination, and intolerable suffering) are now being applied to psychiatric disorders, despite lack of any agreement that treatment for psychiatric disorders are ever futile or that suffering is truly irremediable.29

Concluding Thoughts

Bill C-7 and similar laws would represent a remarkable shift in the deep ethos of psychiatry, in which psychiatrists would have to decide which suicides should be prevented and which should be abetted.

Karandeep Sonu Gaind, MD, past president of the Canadian Psychiatric Association and a fierce critic of the MAID expansion to psychiatric patients, noted that less privileged patients have a much harder time accessing medical care in general, especially psychiatric treatment. He lamented the passing of C-7 in a poetic cri de coeur30:

So thank you Canada, powers that be,

For ensuring that our smooth passings

Will reflect the privilege of our life trappings.

I will soon be free, without anxiety, knowing

That with ease I can choose the time of my going.

And any poor souls sacrificed on this altar

Of my choice, my voice,

There will be no way of knowing.

Dr Komrad is a psychiatrist on the clinical and teaching staff of Sheppard Pratt Hospital and the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland; a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland; and a member of the teaching faculty at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana.

References

1. Komrad MS. A psychiatrist visits Belgium: the epicenter of psychiatric euthanasia. Psychiatric Times. June 21, 2018. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychiatrist-visits-belgium-epicenter-psychiatric-euthanasia#

2. du Bus C. Euthanasia in Belgium: analysis of the 2020 Commission Report. European Institute of Bioethics. November 16, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.ieb-eib.org/en/news/end-of-life/euthanasia-and-assisted-suicide/euthanasia-in-belgium-analysis-of-the-2020-commission-report-1921.html

3. Annual Report 2019. Regional Euthanasia Review Committees. April 2020. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.euthanasiecommissie.nl/binaries/euthanasiecommissie/documenten/jaarverslagen/2019/april/17/index/RTE_jv2019_ENGELS_gecorrigeerd.pdf

4. Komrad MS. APA position on medical euthanasia. Psychiatric Times. February 25, 2017. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/apa-position-medical-euthanasia

5. Komrad MS. Medical euthanasia in Canada: current issues and potential future expansion. Psychiatric Times. June 29, 2018. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/medical-euthanasia-canada-current-issues-and-potential-future-expansion

6. Schadenberg A. There have been approximately 19,000 euthanasia deaths in Canada. Euthanasia Prevention Coalition. October 20, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2021. http://alexschadenberg.blogspot.com/2020/10/there-have-been-approximately-19000.html

7. Health Canada. First annual report on medical assistance in dying in Canada, 2019. July 2020. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/medical-assistance-dying-annual-report-2019.html

8. Rousseau S, Turner S, Chochinov HM, et al. A national survey of Canadian psychiatrists’ attitudes toward medical assistance in death. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(11):787-794.

9. Marin S. Quebec court invalidates parts of medical aid in dying laws as too restrictive. Toronto Star. September 11, 2019. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2019/09/11/quebec-court-invalidates-portions-of-medical-aid-in-dying-laws-as-too-restrictive.html

10. First session, forty-third Parliament, House of Commons of Canada. Bill C-7: an act to amend the Criminal Code (medical assistance in dying). first reading February 24, 2020. Parliament of Canada. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-1/bill/C-7/first-reading

11. Chaimowitz G, Freeland A, Neilson GE, et al. Medical assistance in dying. Canadian Psychiatric Association. February 10, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.cpa-apc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020-CPA-Position-Statement-MAID-EN-web-Final.pdf

12. Bryden J. Senators amend MAID bill to put 18-month time limit on mental illness exclusion. CTV News. February 9, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/senators-amend-maid-bill-to-put-18-month-time-limit-on-mental-illness-exclusion-1.5302151

13. Bryden J. Canadian Senate passes Bill C-7, expanding assisted dying to include mental illness. Global News. March 17, 2021. Updated March 19, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://globalnews.ca/news/7703262/canada-senate-passes-bill-c-7/

14. Smith W. Euthanasia spreads in Europe: several nations find themselves far down the slippery slope. National Review. October 26, 2011. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.nationalreview.com/2011/10/euthanasia-spreads-europe-wesley-j-smith/

15. Boztas S. Euthanasia law proposed for healthy over-75s who feel their lives are complete. Dutch News.nl. July 19, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.dutchnews.nl/news/2020/07/euthanasia-law-proposed-for-healthy-over-75s-who-feel-their-lives-are-complete/

16. Cohen-Almagor R. Euthanizing people who are “tired of life.” In: Jones DA, Gastmans C, MacKellar C, eds. Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide: Lessons from Belgium. Cambridge University Press; 2017:188-201.

17. Clusky P. Euthanasia debate in Netherlands takes an unwelcome twist. The Irish Times. September 10, 2019. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/europe/euthanasia-debate-in-netherlands-takes-an-unwelcome-twist-1.4013718

18. Cook M. A new Swiss group caters for Dutch who are eligible for euthanasia. BioEdge. January 24, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.bioedge.org/mobile/view/a-new-swiss-group-caters-for-dutch-who-are-not-eligible-for-euthanasia/13673

19. Maher J. Why legalizing medically assisted dying for people with mental illness is misguided. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. February 11, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/opinion/opinion-assisted-dying-maid-legislation-mental-health-1.5452676

20. Neves P. Disability is not a fate worse than death. The Chronicle Herald. March 24, 2021. Updated March 27, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.thechronicleherald.ca/opinion/local-perspectives/patricia-neves-disability-is-not-a-fate-worse-than-death-567935/

21. Quinn G, Mahler C, De Schutter O. Mandates of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities; the Independent Expert on the enjoyment of all human rights by older persons; and the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. United Nations Human Rights: Office of the High Commissioner. February 3, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoadPublicCommunicationFile?gId=26002

22. Ruck A. First Nations leaders say Bill C7 goes against their beliefs and values. Canadian Catholic News. February 12, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://grandinmedia.ca/first-nations-leaders-say-bill-c7-goes-against-their-beliefs-and-values/

23. Ruck A. Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops denounces assisted suicide law. The Dialog. April 9, 2021. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://thedialog.org/respect-life/canadian-conference-catholic-bishops-denounces-assisted-suicide-law/

24. Verhofstadt M, Van Assche K, Sterckx S, et al. Psychiatric patients requesting euthanasia: guidelines for sound clinical and ethical decision making. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2019;64(May-Jun):150-161.

25. Lemmens T, Shariff M, Herx L. How Bill C-7 will sacrifice the medical profession’s standard of care. Policy Options. February 11, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/february-2021/how-bill-c7-will-sacrifice-the-medical-professions-standard-of-care/

26. Ethics: euthanasia. code of medical ethics opinion 5.8. American Medical Association. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/euthanasia

27. WMA declaration on euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. World Medical Association. November 13, 2019. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/declaration-on-euthanasia-and-physician-assisted-suicide/

28. Schadenberg A. Washington State debates bill to expand assisted suicide law. say no to same day death. Euthanasia Prevention Coalition. January 11, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://alexschadenberg.blogspot.com/2021/01/washington-state-debates-expansion-of.html

29. Gaind KS. What does “irremediability” in mental illness mean? Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(9):604-606.

30. Gaind KS. Last rights. Karandeep Sonu Gaind. March 11, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5387fe39e4b095eb4a02b4ac/t/604bcc0f49c07e3e0e1e5afd/1615580176126/LAST+RIGHTS+-+FIN.pdf ❒