A new phase for green investing

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is senior adviser to the chief executive of UBS and a former adviser to ex-Bank of England governor Mark Carney

A battle is raging across finance about the best way to invest in the green transition. And the COP26 summit just raised the stakes through the announcement of a new International Sustainability Standards Board for accounting.

Investors will increasingly be able to construct comparable metrics on carbon footprints, throughout the entire value chain and across a whole portfolio. This means that we are heading for a new phase of climate-aligned investing.

Up until now, this has been guided for many by several green rules of thumb. But these may be about to change.

The first phase, before firms started making commitments, was largely thematic: think betting on renewables and being underweight — or excluding — fossil fuels in portfolios.

This strategy has paid off in the past decade in many ESG portfolios. Broadly diversified low carbon intensity portfolios outperformed the wider market by 0.9 per cent a year between 2010 and 2020 or by 2.4 per cent in Europe, according to UBS Research, although numerous factors have been at work.

More recently, a second phase has been characterised by net zero commitments, which have become an important proxy for investors that inform the cost of capital. A working paper by US think-tank FCLT suggests that firms issuing green bonds with a net zero policy enjoyed a 0.08 percentage point “greenium” in terms of better pricing than those which did not.

But “there are no relationships or equations that always work”, my former colleague Barton Biggs, the investment strategist, used to say.

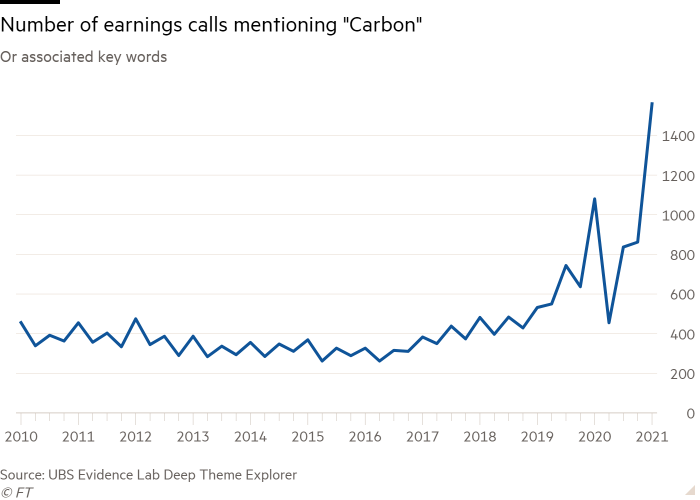

The usefulness of a net zero policy as a heuristic is unlikely to remain. A flurry of firms have announced net zero policies this year and joined Mark Carney’s alliance of financial companies making commitments on climate change.

Big thematic bets also require getting the timing, and thesis, right: investors lost nearly half of the $25bn in clean energy venture capital bets between 2006 and 2011, according to data provider PitchBook.

Getting it right in this next phase will demand more of investors in terms of data, metrics, risk tolerances and governance.

First, investors will need to shift their focus from a top-down view of the overall sector, to a more bottom-up sense of how individual businesses can abate their carbon footprint. This kind of approach will be mirrored by auditors, financial regulators and customers which will seek more detailed data to hold firms accountable.

Part of the new armoury will have to be more forward-looking assessments of how well management teams are tackling climate change and what innovations they are relying on.

Richard Manley of CPP Investments, the manager of the Canada Pension Plan, has proposed an intriguing idea that could significantly sharpen investor understanding: that firms should conduct an annual Abatement Capacity Assessment, cataloguing their capacity to abate greenhouse gases under three headings: current, long-term and uneconomic.

Better data will also enable greater engagement or activism. Some of the most polluting assets are being taken private without any reduction in real world actual emissions. This is simply “paper decarbonisation”. Investors will need better data and comparable metrics if they are to hold boards accountable.

And critically, investors will also need to rethink the playbook of an inflation-protected and diversified portfolio. During previous periods of inflation, energy companies have tended to outperform the broader equity markets.

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here.

In the 1970s, oil and gas companies were up well over 100 per cent in real terms while the S&P 500 dropped. A similar scenario played out between 2000 and 2010. In the 2000s, renewables were a good hedge for being underweight oil and gas assets, according to a report by fund manager GMO.

But the current energy crisis and sell-off in long bonds means that this time it is likely to be different. The oil and gas stock ETF is up 101 per cent in the past 12 months versus just 18 per cent for the global clean energy ETF.

Climate change has brought a new level of complexity to the scenarios that investors need to weigh up. The transition tailwinds will provide them with large investment opportunities for decades.

As climate risk analysis of companies and portfolios moves out of a specialised niche and into the mainstream, savvy investors will need to arm themselves with better climate metrics and new heuristics to construct a climate-aligned portfolio.

Comments