In some countries, voting is compulsory and failure to show up at the polls can be penalized, often with a fine.

But in Venezuela the penalty can be more severe than most: If you don’t vote, you don’t eat.

“For the ones that don’t vote, there is no food,” Diosdado Cabello, one of embattled President Nicolas Maduro’s most powerful allies, said during a campaign rally on Monday. “Whoever does not vote, does not eat. A ‘quarantine’ without food will be applied,” he repeated to a cheering crowd.

Venezuelans will head to the polls on Sunday as the country elects a new parliament, known in the country as the National Assembly. Currently led by opposition leader Juan Guaidó, who is recognized by more than 60 countries – including the United States – as the interim President of Venezuela, the National Assembly is widely seen as the last democratically elected body in the country.

Many wanted to believe Cabello’s remarks ahead of the vote were merely a jest, but it didn’t take long for the message to disseminate among his most feared followers, the armed paramilitary groups known as “colectivos.”

These criminal gangs plague some of Venezuela’s poorest neighborhoods and have played a growing role in keeping Maduro in power. In the barrio of Petare, Venezuela and Latin America’s largest slum, residents say soon after Cabello’s speech, they started receiving threats.

“They came around and told us a bus would come and pick us up, to take us to the polling station,” a woman who asked not to be identified for fear of reprisal told CNN.

“They said if I didn’t come, I would stop receiving my CLAP box,” she added, referring to a box of subsidized essential goods such as flour and rice that the Venezuelan government occasionally distributes among the poorest in the country.

Why should we care?

Sunday’s election happens against the backdrop of one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world. The World Food Program says one in three Venezuelans struggles to put enough food on the table and, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, almost 5 million Venezuelans have left the country, fleeing not just hunger but violence and persecution.

Crippled by years of mismanagement and US sanctions, the Venezuelan economy is still in a downward spiral, mostly because output from the country’s oil industry – which according to the OPEC account for 99% of its exports – continues to decrease.

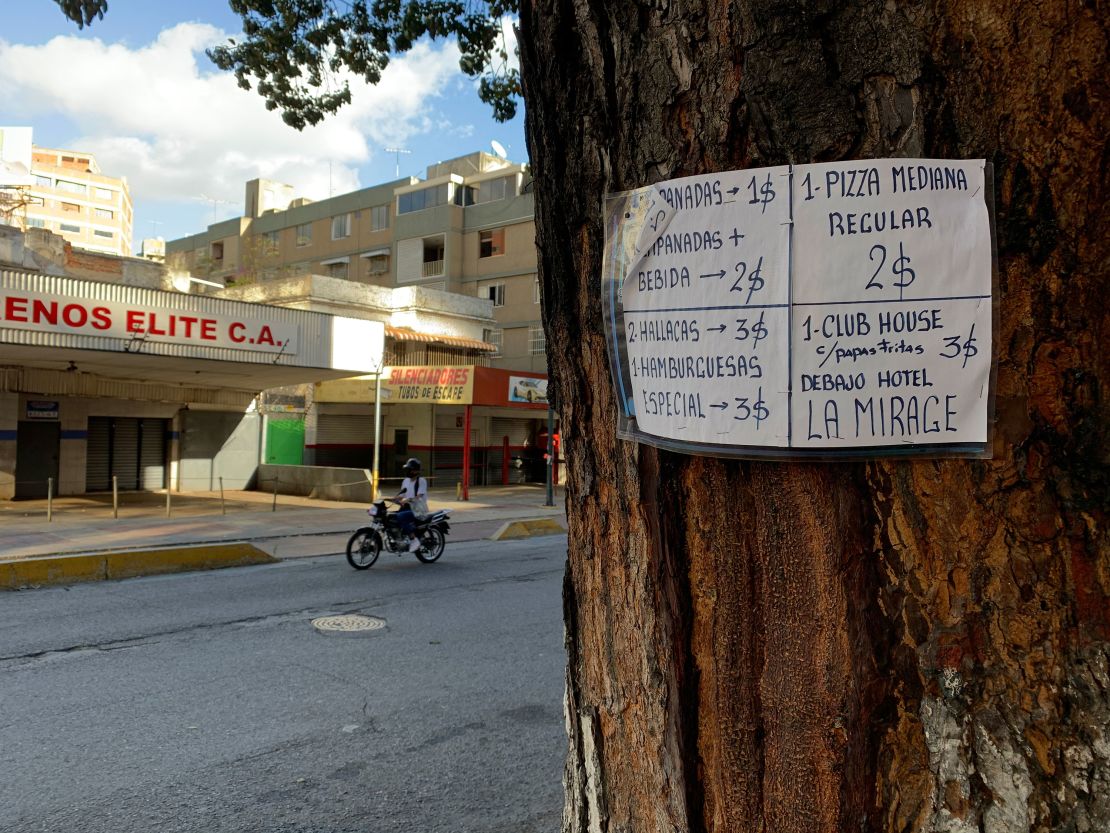

Heading in the opposing direction, inflation reached 4,087%. Across the country, the dollar has now replaced the Bolivar as the main currency, and businesses once afraid of advertising their products in the American currency now do it openly. Even in Venezuela’s barrios, the dollar is now king.

What’s going to happen Sunday?

Despite its status as the only elected body mounting an opposition to Maduro, turnout for Sunday’s election is still expected to be quite low, as the main opposition candidates have withdrawn and called on the people to boycott the vote.

They cite the absence of observers from the United States and the European Union, but also the decision by the government-controlled Supreme Court, which removed Guaidó and others from the leadership of their own parties, replacing them with lawmakers with known ties to Maduro.

“On the 6th of December there isn’t an election, there’s fraud,” Guaidó said on Thursday, calling on people to vote for his “Popular Consult” instead, a rival plebiscite he and his allies are organizing on December 12.

“Participation on the 6th of December is to vote for a fraud; it’s collaborating with the dictatorship,” he added, but recent polls suggest his initiative is also not likely to draw a high participation.

Maduro, on the other hand, has called on people to come out and vote, vowing to leave the presidency if his United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) does not win the election.

“I reiterate to the Venezuelan opposition, I accept the challenge, if they win the parliamentary elections this December 6, I will leave,” he said in a televised speech on Tuesday. “But if we win, let’s go ahead with the people to continue working and deepening the great transformations that the Homeland requires.”

That is an unlikely outcome given how the embattled Venezuelan president stacked the odds in his favor, effectively removing the opposition from contention and threatening the most vulnerable into voting on Election Day.

What does it mean for the opposition?

As Maduro prepares to take over the last democratically elected body in Venezuela, it is still uncertain what this means for Gaidó’s claim to the presidency.

Some of his allies say he will remain the interim President of Venezuela, a position to which he was appointed under the Venezuelan Constitution after the 2018 presidential election gave Maduro a second term. The voting results were widely dismissed as fraudulent by the European Union, the United States, the Organisation of American States and other groups.

Almost two years since he began on his path to overthrow Maduro’s government, Guaidó seems to have lost some of the support of many who still want the country to change.

“People don’t feel that he represents a solution,” a pro-opposition union leader told CNN. “And what the people need is solutions.”