- India

- International

Tuber troubles: Punjab’s potato growers fume over minimum export price condition

Timing of Centre’s move to impact the state’s farmers who supply two-thirds of India’s seed potato requirement.

Potato farmers in Punjab are an angry lot, ahead of the main rabi crop planting season starting early October. The trigger for it is the imposition of a $360 per tonne minimum export price (MEP) on the starchy tuber by the Centre, effective from July 26.

The restriction — not permitting exports of potatoes at a price below Rs 24 per kg from the point of shipment after adding loading costs — is seen to hit Punjab hard. The reason for that is not because it is a big producer — the state has a less than 5 per cent share in India’s annual potato output of 48 million tonnes (mt) — but on account of being a major supplier of the crop used as ‘seed’ by farmers in Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and elsewhere.

Potatoes are mostly propagated by vegetative methods; the ‘seeds’ that growers use are the tubers having nodes or ‘eyes’ from which the stems (sprouts) grow into new plants. Out of Punjab’s total 2.2 mt production, as much as 1.5 mt comprises seed potatoes. This 1.5 mt, produced in 90,000-odd hectares in the four Doaba region districts of Jalandhar, Kapurthala, Hoshiarpur and Nawanshahr, meets nearly two-thirds of the country’s seed potato requirement.

(About 150 kg of seed tuber is required for production of 1,000 kg of regular table potatoes, which, for 48 mt, works out to 7.2 mt. Since farmers need to use fresh seeds only once in three years in any given plot, the actual requirement is 2.4 mt, of which 1.5 mt or 62.5 per cent comes from Punjab)

“The MEP reduces the quantity of potatoes that can potentially go out, thereby creating a surplus crop in the domestic market and impacting overall price sentiment as well. It also lowers demand for our seeds because when prices fall, farmers choose to use their unsold crop itself as seed, even if this leads to less output,” notes Jaswinder Singh Sangha, general secretary of the Jalandhar Potato Growers’ Association.

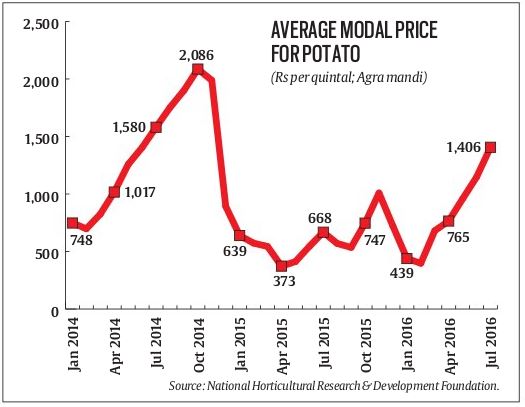

The current government at the Centre had earlier clamped an MEP of $450 per tonne on potato shipments on June 26, 2014, when domestic prices were on the rise. But with prices crashing on the back of a bumper crop — production rose from 41.56 mt in 2013-14 to 48.01 mt the following year — the MEP was removed on February 20, 2015. It is back again at even lower levels (making exports all the more restrictive), as prices have resumed their upward climb since April following a poor crop. That, in turn, has resulted from farmers planting less area on account of low producer prices through 2015 and early 2016.

“You’ll see the same cycle now repeat itself. Farmers were enthused to sow more this time because of higher prices, but the latest MEP imposition will dampen that. We will be particularly affected, as the orders for our material are mostly placed during August-September,” adds Sangha.

Jalandhar is home to large seed potato producers like Sangha Farms, Bhatti AgriTech and JS Farms, each cultivating them on a few thousand acres of both owned as well as leased land. Sowing of the tubers happens during early-October and harvesting towards February-March, after which they are put in cold stores. At 8-10 tonnes per acre, seed potato yields are below the 12-14 tonnes for normal table potatoes. But while the latter sell at Rs 1,000-1,200 per quintal, seed potatoes fetch rates of Rs 2,500-3,000 for branded and Rs 1,800-2,000 for unbranded material.

According to JS Minhas, head of the Central Potato Research Institute’s regional station at Jalandhar, the deep sandy loam soils of the Doaba belt, which falls between the Sutlej and Beas rivers, are best suited for seed potato cultivation. “The period from October to December is also relatively free of aphid attacks. In December, the leaves of the potato plant are cut, even while the tuber remains inside the earth. That further reduces the possibility of infection from any virus from outside,” he states.

Some of the bigger farmers are even growing the seeds in net houses and through tissue culture, which allows for production of practically disease-free material. “During the mid-nineties to the early 2000s, other states stopped taking our seed. They sought to develop seeds from their own crop, the seeds for which we had supplied. But those experiments proved unsuccessful and they went back to procuring seeds from us,” claims Sangha. But for now, Punjab’s seed potato growers are feeling the heat. The viability of their operations rests on realisations for regular potatoes being above Rs 1,000 per quintal. When there is not much demand for their material, as farmers in other states cannot afford to plant new seeds, growers in Punjab have no option but to dispose of these at huge loss. “You cannot keep the crop in cold stores when the monthly rentals are Rs 22-23 per quintal. And where will you keep the next crop if the previous stored crop is not emptied?”, quips Sangha.

Punjab has some 560 cold stores, from where about 1.1 mt of seed are dispatched to other states and 0.4 mt used by table potato growers within the state. There was some hope for seed growers when regular potato prices were beginning to firm up after a more than year-long slump.

But the latest MEP imposition seems to have put paid to that.

May 12: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05