In response to rising inflation, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) tightened monetary policy significantly in 2022, raising the target federal funds rate to 4.25–4.50 percent as of December. Nonetheless, inflation has remained persistently high. Many policymakers expect changes in the federal funds rate—the FOMC’s primary policy tool—to affect the macroeconomy with a lag. However, since 2009, the FOMC has also employed additional monetary policy tools. Financial markets may react to changes in forward guidance on the future path of the federal funds rate and changes in the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet even before the FOMC changes the federal funds rate, suggesting lags in policy transmission may have shortened since 2009.

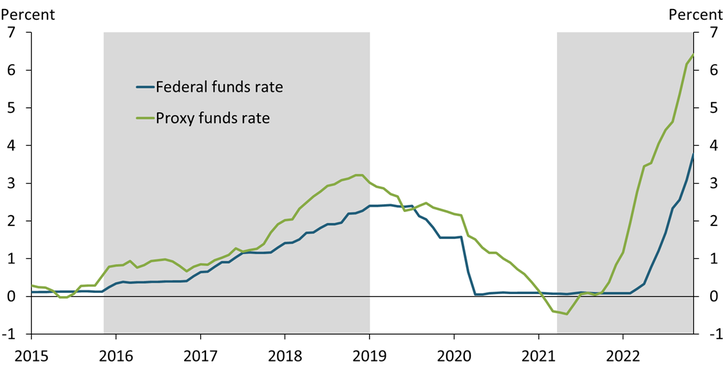

To better capture the stance of monetary policy beyond the federal funds rate, we use an alternative measure—a proxy federal funds rate—that incorporates the effects of forward guidance and balance sheet policy. This proxy funds rate, originally developed by Doh and Choi (2016) and recently updated by Choi and others (2022), uses public and private borrowing rates and spreads to measure the monetary policy stance. If financial market conditions tighten as policymakers provide forward guidance, the proxy fund rate can rise, even if policymakers have not raised the federal funds rate._ For example, Choi and others (2022) note that the proxy funds rate had already risen to about 2 percentage points in February 2022 before the FOMC increased the actual target for the federal funds rate in March from the 0–0.25 percentage point range.

Chart 1 shows that the proxy funds rate (green line) has been consistently above the effective federal funds rate (blue line) during recent tightening episodes (December 2015 to December 2018 and March 2021 to present)._ The gap between the proxy and federal funds rate highlights that the federal funds rate may not capture the full degree of policy tightening in the economy; thus, policymakers relying only on measures of the funds rate may overestimate lags in policy transmission. In other words, if inflation is responding to the broader stance of policy (as captured by the proxy funds rate) rather than just the federal funds rate, then the lags in transmission from monetary policy stance measured solely by the federal funds rate to inflation may be shorter today than was the case pre-2009.

Chart 1: The proxy funds rate has been higher than the effective federal funds rate during recent policy tightening (2015–18 and 2021–22)

Notes: Gray bars represent tightening episodes. Data are through November 2022.

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and authors’ calculations.

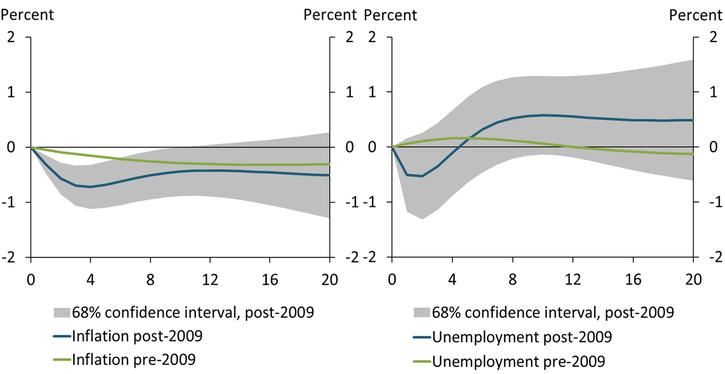

Another way lags in policy transmission may have changed after 2009 is if macroeconomic variables react faster to changes in forward guidance, which may signal a more persistent change in financial market conditions. To investigate this possibility, we estimate a statistical model describing the dynamic relationships of core PCE inflation, the unemployment rate, and the proxy funds rate for two subsample periods: pre-2009 and post-2009. We select 2009 as the breakpoint because the FOMC increasingly used forward guidance and balance sheet policy after the federal funds rate reached the effective lower bound in December 2008. Chart 2 shows the mean estimates for the dynamic responses of inflation and unemployment to a monetary policy shock identified by an unexpected one percentage point tightening in the proxy funds rate during the pre- and post-2009 periods (green and blue lines, respectively)._

Chart 2: Macroeconomic responses to an unexpected policy tightening, pre- and post-2009

Notes: Inflation denotes core PCE inflation. The horizontal axis represents quarters after the realization of a one percentage point shock to the proxy funds rate while the vertical axis represents a percent change in its response. The confidence interval is calculated based on the post-2009 data.

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (both accessed through FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis), and authors’ calculations.

Compared with the green lines, the blue lines in Chart 2 suggest that the lags in monetary policy transmission have indeed shortened since 2009. In the pre-2009 period (green lines), an unexpected one percentage point tightening in the proxy funds rate reduces inflation and increases unemployment; however, the peak response of inflation occurs with a significant lag of more than three years (12 quarters). In contrast, in the post-2009 period (blue line), the peak response of inflation is larger and happens after only four quarters, suggesting changes in financial market conditions may affect prices sooner than in the pre-2009 period. However, the confidence intervals for the post-2009 period (gray shaded areas), which measure the degree of uncertainty in the sample, are high, especially when the horizon extends beyond eight quarters after the realization of a shock. The uncertainty associated with the response of unemployment to a policy shock is so high in the post-2009 period that it overlaps the pre-2009 estimates; thus, we do not find statistically significant evidence that the unemployment response has changed._

In summary, we find evidence for a shorter lag in the peak response of inflation to a policy shock in the post-2009 period even after we adjust the shock definition to incorporate forward guidance and balance sheet policy. Our results suggest the peak deceleration in inflation may occur about one year after policy tightening. However, the uncertainty associated with the response of inflation is high in the post-2009 period. In addition, given high uncertainty, we do not find any statistically significant evidence that unemployment response to policy tightening has changed during the recent period.

Download Materials

Endnotes

-

1

Additionally, unlike the federal funds rate, which is restricted by the zero lower bound, the proxy funds rate can fall below zero to account for effects on rates that govern private borrowing conditions, where the effective lower bound is less likely to be binding.

-

2

The proxy funds rate data are available from June 1976, and the more extensive comparison between the proxy funds rate and the effective federal funds rate is shown in Choi and others (2022).

-

3

We take the three-month average of the core PCE inflation from a year ago, the unemployment rate, and the proxy funds rate to transform the monthly frequency to the quarterly frequency. We fit a vector autoregression of order 2 for the three variables and put the proxy funds rate last to identify a policy shock from the recursive ordering assumption. The recursive ordering imposes the restriction that the proxy funds rate responds contemporaneously to unexpected developments in inflation and unemployment while macro variables respond to a surprise in the proxy funds rate only with a lag.

-

4

Although the same size monetary policy shock generates bigger macroeconomic responses during the post-2009 period, the variance of a monetary policy shock is much lower in the post-2009 period. In other words, a monetary policy shock of 100 basis points is much less likely to be realized during the post-2009 period.

References

Choi, Jason, Taeyoung Doh, Andrew T. Foerster, and Zinnia Martinez. 2022. “External LinkMonetary Policy Stance Is Tighter than Federal Funds Rate.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Economic Letter no. 2022-30, November 7.

Doh, Taeyoung, and Jason Choi. 2016. “External LinkMeasuring the Stance of Monetary Policy on and off the Zero Lower Bound.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, vol. 101, no. 3, pp. 5–24.

Taeyoung Doh is a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Andrew T. Foerster is a senior research advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, or the Federal Reserve System.