The Unfulfilled Promise of LGBTQ Rights in South Africa

The country has some of the most progressive laws in the world, but refugees fleeing homophobia elsewhere often find a country that is morally conservative, hostile, and profoundly violent.

CAPE TOWN, South Africa—On a recent foggy morning, Ndodana boarded a minibus and traveled more than 20 miles to the Ivan Toms Centre for Men’s Health to collect his free HIV medication. The gay-friendly clinic lies in a predominantly white neighborhood of Cape Town, wedged between a strip of restaurants, upscale hotels, and the V&A Waterfront, a major tourist attraction.

The bimonthly trip is a long one and, on the surface, unnecessary: Mfuleni, the impoverished township where he rents a room, has its own HIV-treatment center. Yet to Ndodana, a slender, dreadlocked Zimbabwean in his early 30s, going there is not an option. The clinic is run-down and often overcrowded. Most of all, though, he fears harassment for being gay.

“The officials don’t do their jobs,” Ndodana, who asked that he be identified only by his first name to avoid being targeted, told me. “Instead they are judging you.”

When apartheid ended a quarter century ago, South Africa’s new rulers rushed to adopt inclusive legislation, passing laws enshrining gender equality and freedom of expression. The country now has some of the most progressive LGBTQ laws in the world, including full constitutional protections against discrimination. This legal environment is unmatched on a continent where colonial-era laws against gay sex are still commonplace, and where offenders in some nations face the death penalty. Cape Town advertises itself as Africa’s gay capital, with dedicated nightclubs, film festivals, and pride events.

As a result, many LGBTQ people from across the continent make their way here. Hundreds of people who are sexual minorities arrive each year from places such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, and Sudan. In Ndodana’s case, after he fled violent persecution at home in Zimbabwe, South Africa was supposed to offer sanctuary—a place to live, and love, with almost unimaginable freedom.

But like countless others in his position, he soon came to see a wide gulf between this legal promise and the lived reality. The rights promised on paper in South Africa remain out of reach for many who need them most, particularly those fleeing homophobia elsewhere. For them, a quite different South Africa awaits: morally conservative, hostile to outsiders, and often profoundly violent. “The law jumped miles ahead of society,” said Nigel Patel, an LGBTQ-rights activist who moved to South Africa from Malawi, in part for this country’s queer-friendly reputation.

A recent survey of more than 2,000 LGBTQ people by Out, a South African rights organization, found that within a two-year period, 39 percent had been verbally insulted, 20 percent had been threatened with harm, 17 percent “chased or followed,” and nearly 10 percent physically attacked. About half of all black respondents knew people who had been murdered because of their sexual orientation. In 2011, the justice ministry established a task force to tackle the phenomenon of “corrective rape,” routinely meted out to lesbian women and trans men to “cure” them of homosexuality. In its latest world report, Human Rights Watch flagged LGBTQ rights here as an ongoing concern.

This vulnerability is often compounded for refugees, who must confront the pervasive xenophobia that has left more than 250 foreigners dead, and thousands more displaced, since large-scale violence first erupted in 2008, according to tracking by researchers at South Africa’s Witwatersrand University. Researchers and activists say that this undercuts South Africa’s reputation as a haven for gay rights, a narrative enthusiastically promoted by the government and so-called pink-tourism operators. “Compared to where we’re coming from, it’s better,” says Victor Chikalogwe, who left Malawi after being outed and disowned by his family and who is now the director of PASSOP, a local nonprofit that advocates for refugees and asylum seekers. “But still, it isn’t enough.”

Ndodana is one of many who have fled persecution only to discover that South Africa’s promise of freedom was largely illusory. When he was 8 years old, his mother remarried and sent him to live with an uncle in Silobela, a village north of his childhood home in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe’s second-largest city. Soon afterward, his uncle began sexually abusing him, a pattern that went on for four years. At 13, Ndodana went back to living with his mother, keeping secret what had happened to him. Yet the discrimination didn’t stop upon his return home. At school, children started calling him stabani, a derogatory local term for gay men that he’d never heard before. When he asked his mother what it meant, she slapped him and said, “I don’t want to hear that word in this house.”

Homosexuality is forbidden under Zimbabwe’s constitution, with no legal protections against violence or discrimination. Consensual sex between men can lead to fines or jail terms of up to a year. Homophobia is propagated within churches, the media, and by politicians, with state-sanctioned harassment of gay-rights groups. In 2015, former President Robert Mugabe said on the radio that gay people were “worse than dogs and pigs.”

In high school, Ndodana and several of his friends began wearing wigs to socials, enacting a niche and mostly clandestine culture of cross-dressing in Zimbabwe. “People were thinking it was funny, but I was enjoying it,” Ndodana told me. In 2006, shortly after graduating, he and a friend attended a party wearing dresses, but were arrested by the police on their way home. For a week, Ndodana said, they were “just tortured.” The two were held in cells, beaten with heated metal bars—Ndodana showed me large, smooth scars on both legs—and held down in drums of water. “When you screamed,” he told me, “the water filled your mouth.”

Eventually they were released and dropped at the roadside in Bulawayo. Ndodana’s friend later died from his injuries, and Ndodana’s mother, who is yet to accept his sexuality, urged him to flee to South Africa. “In Zimbabwe,” she told him, “people like you aren’t free.” In early 2007, he jumped the border, wading across the Limpopo River, which divides the two nations.

Since 1998, South Africa has offered asylum to people being persecuted for their sexual orientation, yet the system is flawed and often fails to protect victims. In a report on the “deplorable” experiences of LGBTQ refugees, the Legal Resources Centre, a local nonprofit, notes “systemic problems and inefficiencies” in the application process, many of them owing to prejudice among officials. “They’ll ask you to prove that you’re gay,” said Ethan Chigwada, a PASSOP staffer who escaped from Zimbabwe in 2015 after suffering years of physical and sexual abuse at the hands of family members.

With its comparatively advanced economy and stable government, South Africa receives more than 62,000 asylum requests each year, considerably more than any other African nation. According to a report by the national Department of Home Affairs, more than 90 percent of these applications are rejected. Hundreds of thousands of immigrants, including many who are LGBTQ, remain undocumented. “That’s where the trouble starts,” Chikalogwe, PASSOP’s director, said.

After crossing into South Africa, Ndodana made his way to Cape Town, the city where this country’s extreme wealth inequality is most visible. He eventually moved to a township on the outskirts, where he found work at a supermarket and made friends. But soon he found that his safety was tenuous. On the streets, people would taunt him, calling him a moffie, a local slur for gay people. “You don’t respond—you keep quiet,” Ndodana told me. “If you talk back, you can get hurt.”

In 2008 he applied for asylum, only for an official to laugh at him and say, “A gay in Zimbabwe? There’s no such thing.” Another official asked whether Ndodana wished to queue up as a woman or a man. Dissuaded, he would remain undocumented until four years later, when PASSOP helped him apply once again.

In May 2008, xenophobic violence swept across South Africa, killing 62 people. Ndodana returned home one day to find the house where he was living being looted and set on fire. Afterward, Ndodana said, “the situation became very bad.” He lost his job and sank into a depression, moving in with a friend and spending most of his time indoors. The following year, in desperate need of money, he became a sex worker, but because many of his clients refused to use condoms, he soon contracted HIV. Even then, the discrimination continued—nurses at the nearest clinic refused to treat him unless he brought his partner.

Today, Ndodana shares a small house with four other refugees, three of whom identify as gay. He has painted a pale-blue sky with white clouds across the ceiling of his room—a mural, he says, that brings him “closer to God.” South Africans and Zimbabweans have called him “evil” for his sexuality, but privately he still considers himself Christian. “You keep praying that one day that door will open,” he told me, speaking of the rejection by his religious community.

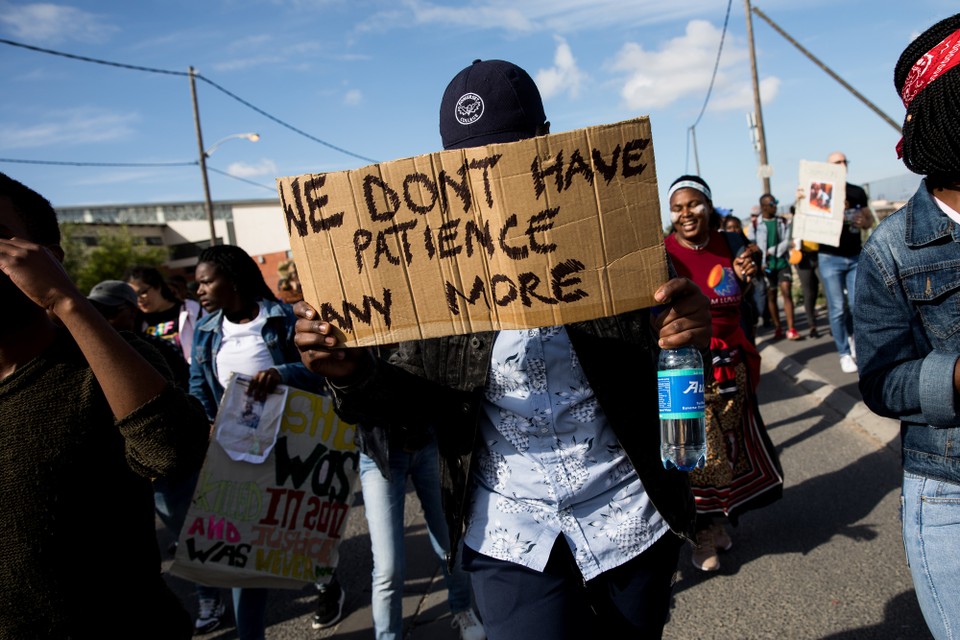

This past May, he attended Kumbulani Pride, an annual event to commemorate victims of homophobia that this year was taking place around the corner from his house. About 200 people marched to a government primary school, where activists lit candles for murdered lesbian women.

In the distance, Table Mountain—around which Cape Town is built—was still visible, marking the city’s wealthier quarters. The gay bars would soon fill up there, with parties extending into the late hours. But by then Ndodana would be at home again, thumbing through pictures on his cellphone.

Most nights he stays indoors, too afraid to go outside.