Public transport has been hit hard by COVID-19. With ridership significantly down, operators in developing cities will have to face difficult questions for their future viability. The appropriate response must plan for contingencies, but never forget the value of shared transit in the process of economic development.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, cities across the world have had to enforce massive restrictions on public transport in order to limit transmission of the virus and ensure safe passage of key workers during the emergency response. Addis Ababa, Lagos, and Johannesburg are just a few of the major cities where public buses have had to run at less than 60% of normal capacity during lockdown. Similar restrictions in Brazil are estimated to have cost bus operators as much as USD188 million in daily fare losses, according to the National Association of Urban Transport. At the same time, most providers are having to spend whatever they can on protecting their passengers and staff. Kigali, Rwanda, for example, has flooded its bus stops with portable sinks and hand sanitisers, at no small expense to the government.

The implications for informal operators

One of the biggest challenges for developing cities, however, is that most public transport is informal and privately owned. In Nairobi, for instance, 70% of commuters rely on privately-operated matatus to get to work. For millions, these unregulated minivans, taxis, or scooters are the only source of motorised travel (often offering a broader and more reliable service than the formal system), not to mention, a significant source of employment.

With informal services largely out of the government’s control, it is difficult for public officials to now turn around and demand pandemic-worthy measures. In South Africa, hundreds of informal minibus operators have defied government attempts to enforce capacity restrictions, complaining that they would make it impossible for them to earn a living. Forcing operators to suspend or reduce services might also put them out of business for good – threatening a vital source of connectivity well into the aftermath of COVID-19.

The implications for public welfare

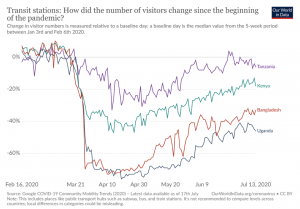

According to data from Google mobility reports, visitors to all public transit locations – such as bus services, terminals, and waiting areas – have fallen by as much as 80% across IGC countries since early March. Many operators have had no choice but to scale back or completely shut down less viable routes; while others are passing their costs onto consumers. While visits have been steadily rising since, the threat of sharp restrictions still loom for many of the poor and disadvantaged who have few alternatives.

The social impacts are undoubtedly significant. While those with access to private cars might enjoy uncharacteristically quiet roads, for poorer households that depend on shared transit, being denied motorised travel for months could have disastrous consequences.

Most low-income residents will have no choice but to walk or cycle, but with added curfews and outdoor time limits, access to work and social services are likely to be severely impeded. Evidence from Nairobi shows that the overall share of job opportunities within one hour of travel, is up to five times higher for those with cars compared to those on shared minibuses or on foot. This not only cuts off low-income households from existing jobs, but also limits their access to new opportunities, risking higher unemployment amongst poor communities, and hurting long-term economic outcomes for both the individuals and the city.

For many countries, social support and work-from-home schemes have been a critical life-line to preserve livelihoods when citizens cannot travel. These are also important because they preserve the value of firm-specific knowledge and skills that employees gain over many years with their employers. But such programmes are extremely challenging in developing country contexts. Not only are they hard to maintain in the face of limited public budgets, but they are also much harder to target when most employment is informal, when few work in industries where home-based work makes sense, and then even if it did, when many lack the physical infrastructure to make it possible.

Do not go from lockdown to gridlock

A final and important consideration is that as developing cities look to re-open, it is vital that they do not go from lockdown to gridlock. Without proper investments in accessibility and public transport, the emerging middle class will increasingly look towards private travel, jeopardising decades of work towards sustainable transport. Recent evidence from European cities shows that pollution and congestion rebounded sharply after the removal of restrictions as commuters shunned shared transport in favour of their cars. Such trends are not only worrisome for their effects on climate change and public health, but also for their overall impacts on economic development.

Decades of research has shown that improved mobility is the key to allowing large-scale economic growth of cities. With very high commuting costs, people live very close to where they work, limiting access to job opportunities and constraining firms to remain local in scope. But when people and products can move efficiently across a city, workers can match with jobs most suited to them, and firms can access markets in ways that allow for large-scale and specialised production.

Few transport modes can promote these synergies as cost-effectively as shared transit. With limited land and resources for construction in many cities, vehicles that can carry more passengers per unit of road space can deliver widespread economic, social, and environmental gains.

Evidence from developing cities shows that public transport investments allow people longer commutes, freeing up urban land for more productive use, and contributing to an intense clustering of economic activity in city centres. The benefits are felt directly by users whose travel times fall, and indirectly by wider society because faster travel leads to lower trade costs which, in turn, decreases overall prices for urban goods and services.

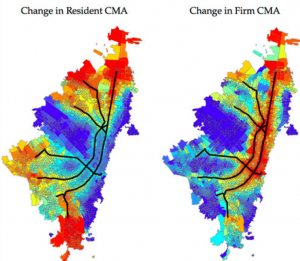

Figure 1

Evidence from Bogota shows how the introduction of the TransMilenio BRT system allowed residential locations (left) to spread to peripheral locations and for firms (right) to cluster intensively into productive central locations around the BRT.

Preparing for a new reality

Economic evidence suggests that reducing accessibility is likely to increase unemployment, weaken access to opportunities, and hurt overall urban productivity. Governments are therefore faced with a very difficult challenge: they need to protect the survival of public transport whilst also ensuring safe mobility during COVID-19.

Part of the response must include efforts to maintain safe and sustainable accessibility in cases where public transport has become less viable. Within the sector itself, improving hygiene standards and reducing load capacities would fall into the equation. Outside of public transit, and particularly in cities where the vast majority of citizens walk or cycle to work, this would include investments in non-motorised travel. Investing in walkways, foot bridges, cycle infrastructure, and street lighting will be critical ways in maintaining accessibility.

For many developing cities, it could also be a good time to think about reorienting the informal network to provide more reliable and increased coverage. This will be a critical part of reviving consumer confidence amongst riders who may fear sharing public space with others. It could also help to ensure their long-term viability. Countries like Uganda are attempting this but with limited success. For these efforts to work, governments need to have a genuine public system for informal workers to transfer into.

Finally, with traffic at unusually low levels, cities have the opportunity to invest in public transit capacity without too much disruption to people’s daily commutes. This includes decisions such as: How to improve road allocation, through e.g. the expansion of preferred bus lanes. How to improve customer experience and safety, through e.g. increased hygiene or digitised ticketing and payment systems. And how to increase capacity, through e.g. the purchasing of equipment or the implementation of Intelligent Transport Systems.

Research from Asian cities hit by SARS, shows that transport ridership actually bounced back relatively quickly after travel restrictions were lifted. The same is true for travel patterns in West Africa after Ebola, and in a slightly different way, the US after 9/11. The fact is that when the dust settles, people will always choose the services that offer best reliability, cost, comfort, safety, and sustainability. Public transit has to be ready to capture this comeback in the market.

This blog is part of a series curated by the Cities that Work initiative exploring topics on cities and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Read more.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.